Third Parties

Introduction

Third parties are ubiquitous on the web. Website developers rely on them to implement key features such as advertising, analytics, social media integration, payment processing, and content delivery. This modular approach enables efficient, rapid deployment of rich functionality. However, it introduces potential privacy, security, and performance concerns.

In this chapter, we conduct an empirical analysis of third-party usage patterns on the web. We examine:

- Prevalence: How many websites use third parties and in what proportions

- Resource types: The forms third parties take (images, JavaScript, fonts, etc.)

- Functional categories: Ad networks, analytics, CDNs, video providers, tag managers, and others

- Integration methods: How third parties are loaded directly or indirectly on pages

- Consent infrastructure: Which third parties handle consent signals and how those exchanges occur in practice

Definitions

First, we establish some definitions and terminology that are used throughout our analysis.

Sites and pages

In this chapter, like previous years, we use the term site to depict the registerable part of a given domain which is often referred to as extended Top Level Domain plus one (eTLD+1). For example, given the URL https://www.bar.com/ the eTLD+1 is bar.com and for the URL https://foo.co.uk the eTLD+1 is foo.co.uk. By page (or web page), we mean a unique URL or, more specifically, the document (for example HTML or JavaScript) located at the particular URL.

What is a Third Party?

We stick to the definition of a third party used in previous editions of the Web Almanac to allow for comparison between this and the previous editions.

A third party is an entity different from the site owner (aka first party). It involves the aspects of the site not directly implemented and served by the site owner. More precisely, third-party content is loaded from a different site (i.e., the third party) rather than the one originally visited by the user. Assume that the user visits example.com (the first party) and example.com includes silly cat images from awesome-cats.edu (for example using an <img> tag). In that scenario, awesome-cats.edu is the third party, as it was not originally visited by the user. However, if the user directly visits awesome-cats.edu, awesome-cats.edu is the first party.

For our analysis, only third parties originating from a domain whose resources can be found on at least 5 unique pages in the HTTP Archive dataset were included to match the definition.

When third-party content is directly served from a first-party domain, it is counted as first-party content. For example, self-hosted analytics scripts, CSS, or fonts are counted as first-party content. Similarly, first-party content served from a third-party domain is counted as third-party content. Some third parties serve content from different subdomains. However, regardless of the number of subdomains, they are counted as a single third party.

Further, it is becoming increasingly common for third parties to be masqueraded as a first party. Two key techniques enable this:

-

CNAME cloaking involves using a CNAME record to make a third party’s content appear to come from the first-party domain. We consider CNAME-cloaked services as first parties in this analysis.

-

Server-side tracking is an emerging trend where the site owner embeds the tracker as a first party and routes all requests through the first-party domain, making the tracker appear as a first party. For example, a website

www.example.commay embed server-side Google Tag Manager with Google Analytics and cloak the subdomainsst.example.comto send requests to a Google Tag Manager Container. In this way, requests to third parties originate from the tag manager’s server rather than the user’s browser.

In our analysis, we treat such cases as first-party interactions because the third-party communication occurs server-to-server and is not directly observable in the client-side HTTP Archive data. As a result, our measurements represent a lower bound on the actual prevalence of third parties on the web

Categories

As previously indicated, third parties can be used for various use cases—for example, to include videos, to serve ads, or to include content from social media sites. Similar to the previous year, to categorize the observed third parties in our dataset, we rely on the Third-Party Web repository from Patrick Hulce. The repository breaks down third parties along the following categories:

- Ad: These scripts are part of advertising networks, either serving or measuring.

- Analytics: These scripts measure or track users and their actions. There’s a wide range of impact here, depending on what’s being tracked.

- CDN: These are a mixture of publicly hosted open source libraries (for example jQuery) served over different public CDNs and private CDN usage.

- Content: These scripts are from content providers or publishing-specific affiliate tracking.

- Customer Success: These scripts are from customer support/marketing providers that offer chat and contact solutions. These scripts are generally heavier in weight.

- Hosting: These scripts are from web hosting platforms (WordPress, Wix, Squarespace, etc.).

- Marketing: These scripts are from marketing tools that add popups/newsletters/etc.

- Social: These scripts enable social features.

- Tag Manager: These scripts tend to load many other scripts and initiate many tasks.

- Utility: These scripts are developer utilities (API clients, site monitoring, fraud detection, etc.).

- Video: These scripts enable video player and streaming functionality.

- Consent provider: These scripts allow sites to manage the user consent (e.g. for the General Data Protection Regulation compliance). They are also known as the ’Cookie Consent’ popups and are usually loaded on the critical path.

- Other: These are miscellaneous scripts delivered via a shared origin with no precise category or attribution.

Content-Type

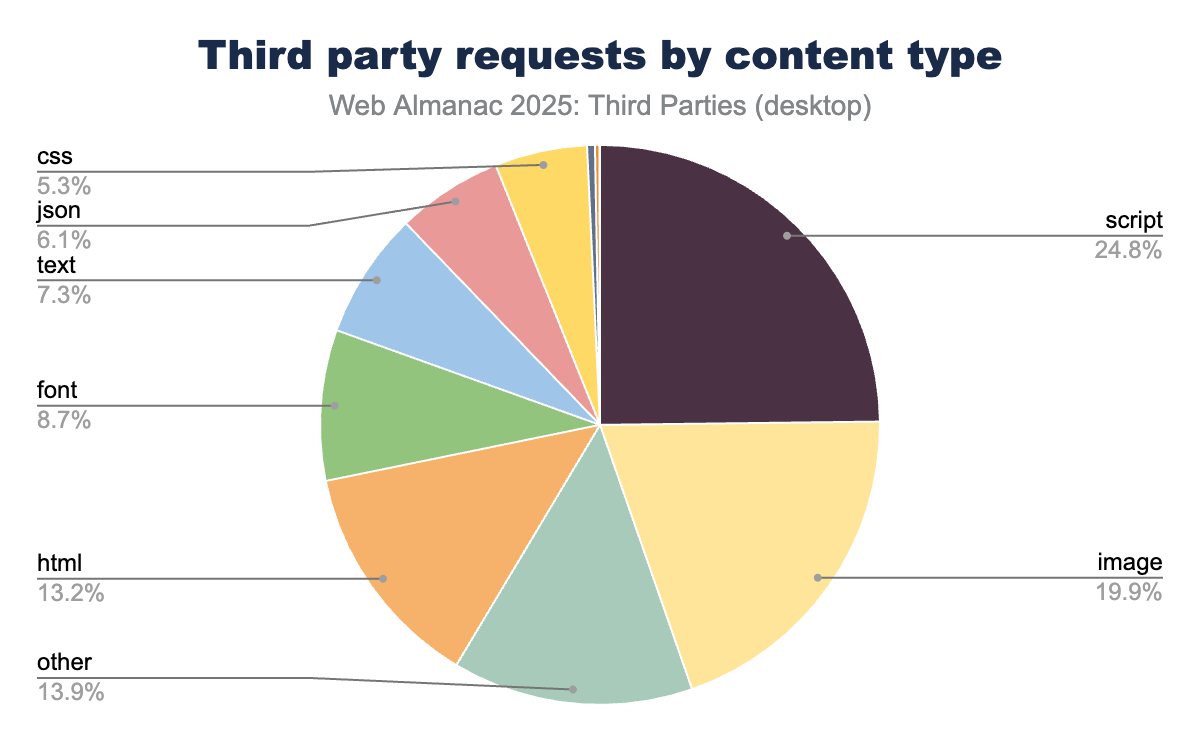

We use the Content-Type HTTP header to categorize third-party resources into different types, such as scripts, HTML content, JSON data, plain text, and images. This allows us to analyze the composition of third-party resources served across websites

Prevalence

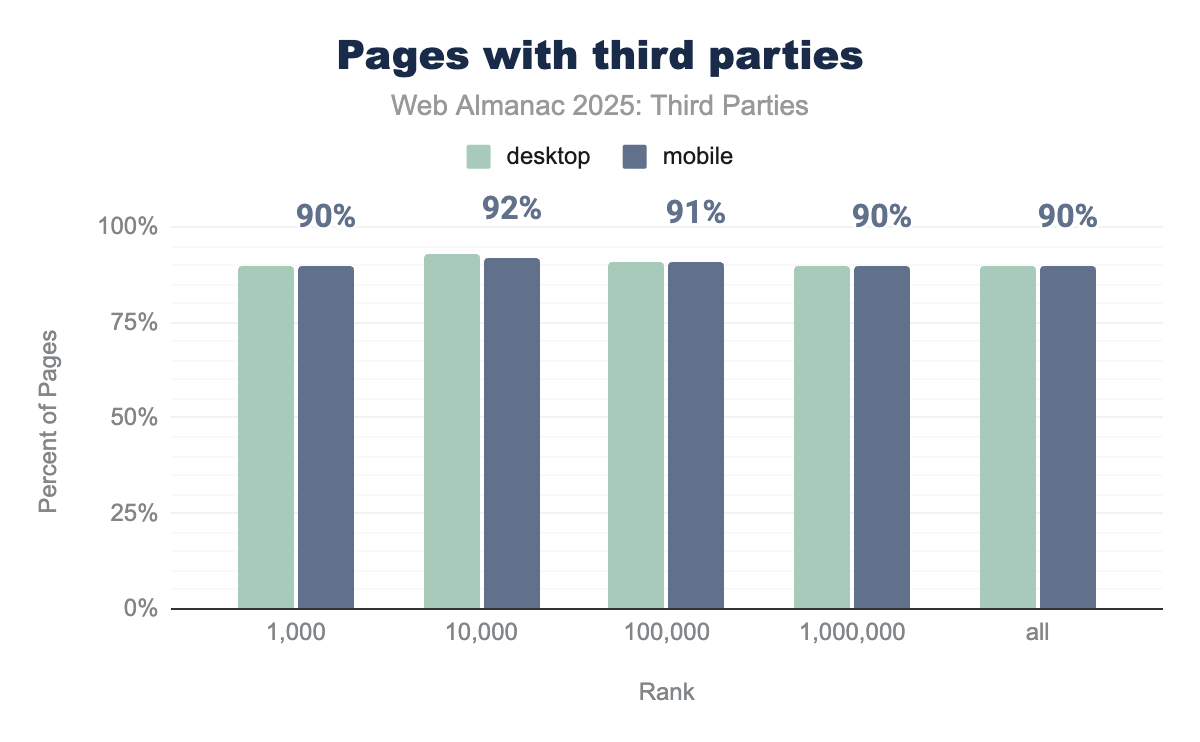

Compared to the previous year, we observe a slight decrease in the percentage of pages that use one or more third parties across websites. However, despite this decrease, the percentage of pages with one or more third parties remain greater or equal to 90%.

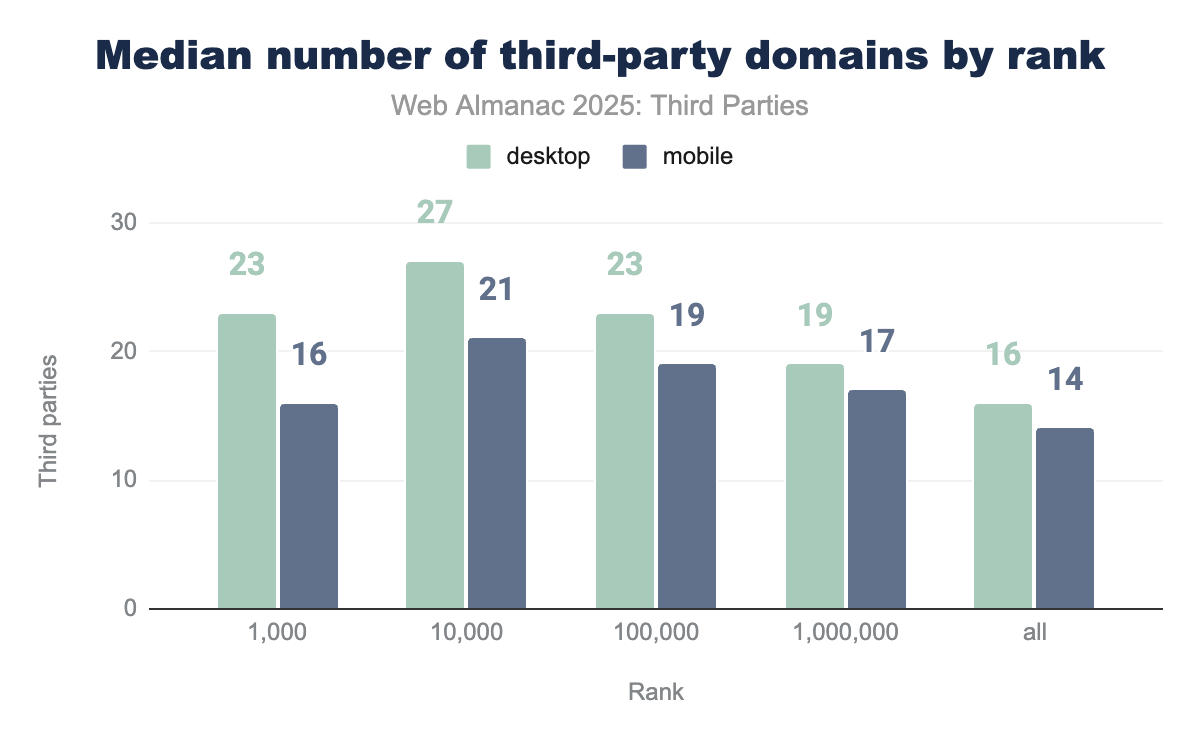

Compared to the previous year, we observe a decrease in the median number of third-party domains across all website ranks.

This decline may be due to several factors. First, third parties are increasingly obscured through CNAME cloaking and server-side tracking, which can reduce their visibility in client-side measurements. Second, our crawlers do not interact with cookie banners during the crawl, which may not generate consent signals. As a result, third parties may not run on a page, resulting in fewer observable third-party requests.

We also observe that desktop pages generally include more third parties than mobile pages.

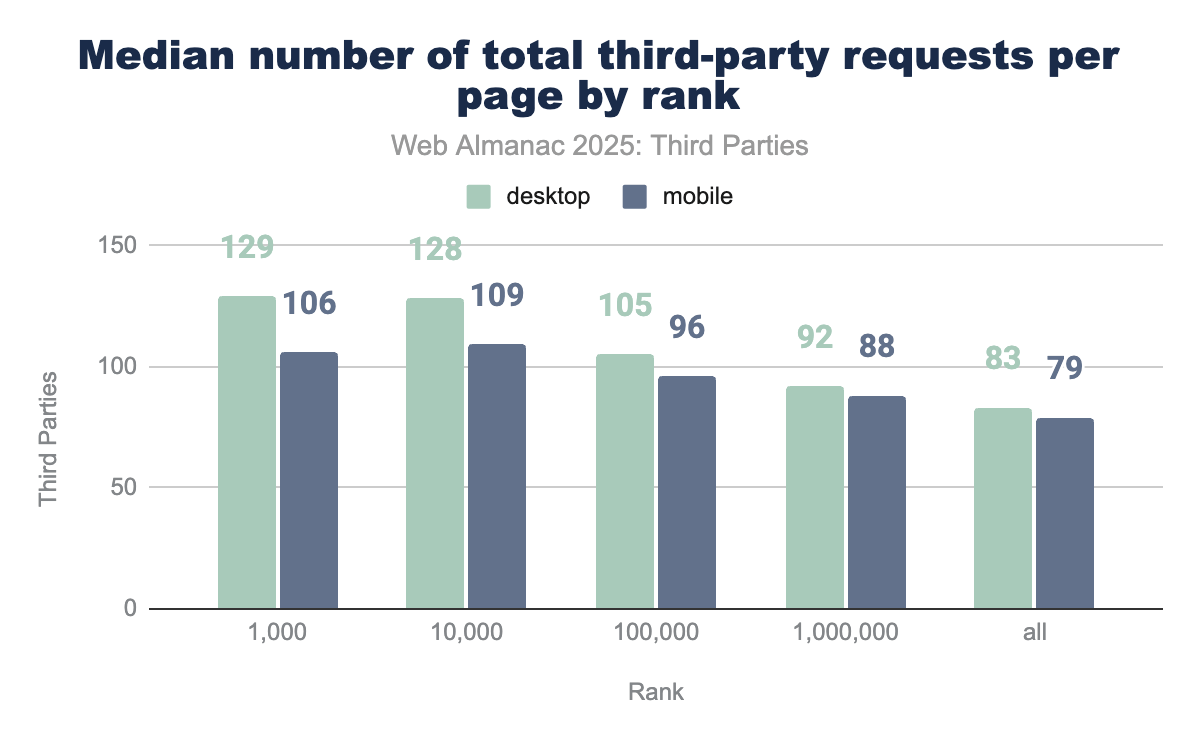

Higher-ranked websites load more third-party requests. The top 1,000 have a median of 129 requests on desktop and 106 on mobile, compared to 83 on desktop and 79 on mobile across all sites.

Year-over-year, third-party requests have increased across all ranks. The top 1,000 sites show an increase of 15 requests on desktop and 15 on mobile compared to 2024, while the broader dataset increased by 5 requests on desktop and 5 on mobile. This upward trend occurs despite the decrease in the number of unique third-party domains we observed earlier, suggesting that individual third parties are sending more requests per page.

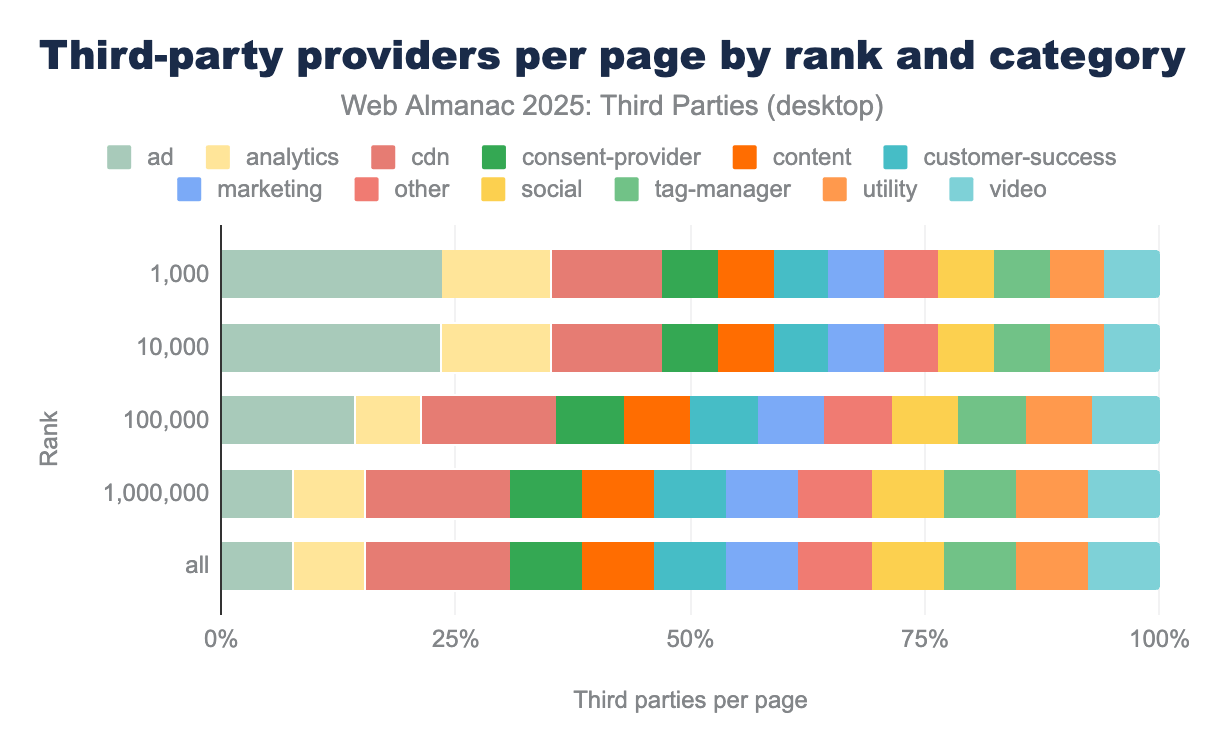

The top categories include ad, analytics consent-provider and other categories.

script (24.8%), image (19.9%), and other (13.9%)The top 3 types include script, image, and other.

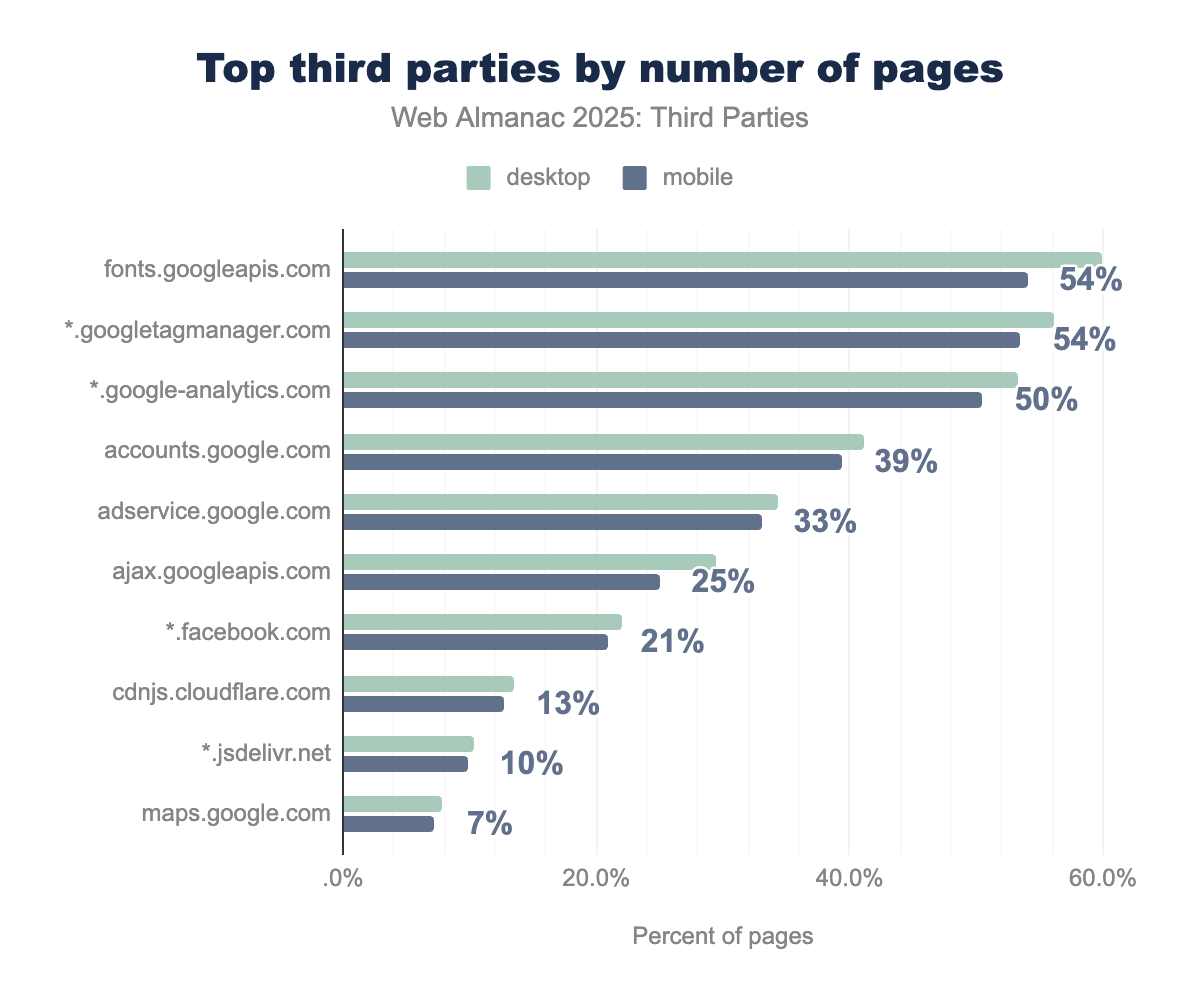

The top 10 third-party domains are dominated by Google-owned services, including fonts.googleapis.com, googletagmanager.com, google-analytics.com, accounts.google.com, and adservice.google.com. Meta’s facebook.com is the only non-Google domain in the top 10, appearing at rank 7 with 21% of pages.

Consent propagation among third parties

In this section, we examine how different third parties transmit user consent across the web. Previous research has shown that third parties often rely on industry-standard frameworks to communicate consent information. In our analysis, we focus primarily on the IAB’s consent standards, including the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF), the CCPA Compliance Framework, and the Global Privacy Platform (GPP).

These frameworks define how consent information should be encoded and shared. For example, the IAB CCPA framework specifies that consent strings should be transmitted using the us_privacy parameter in network requests. We begin by identifying which consent standards are most prevalent among third parties observed in our dataset.

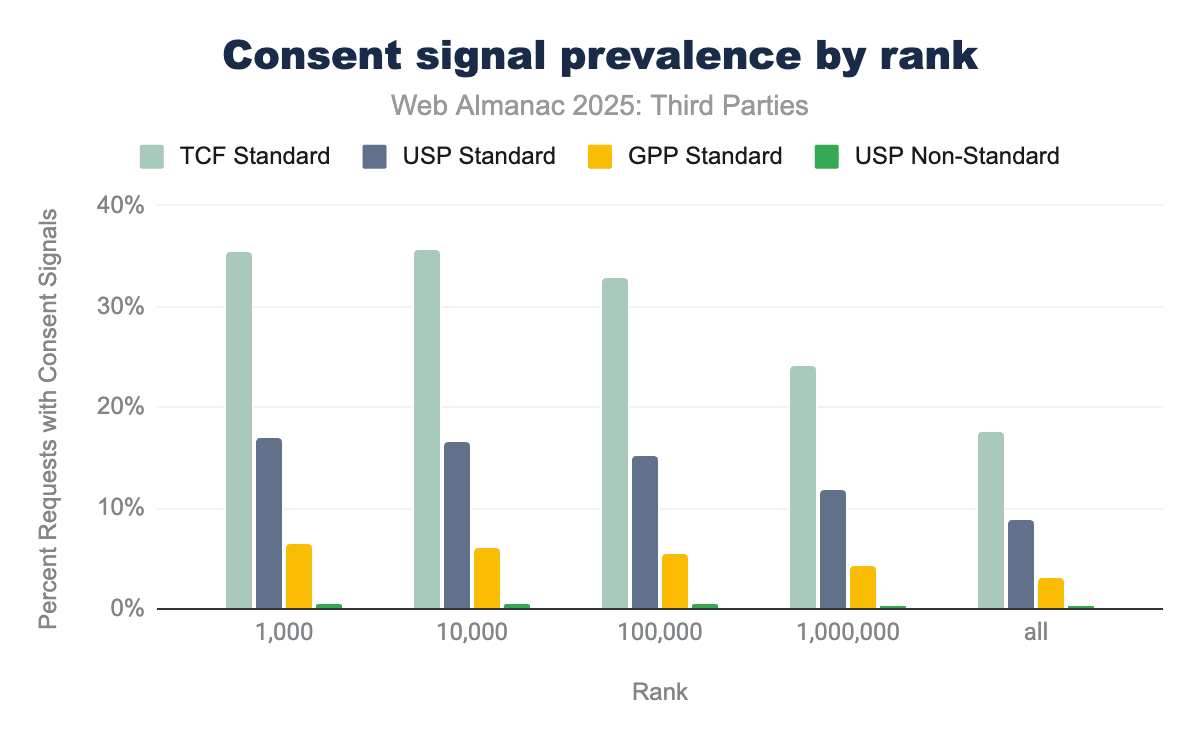

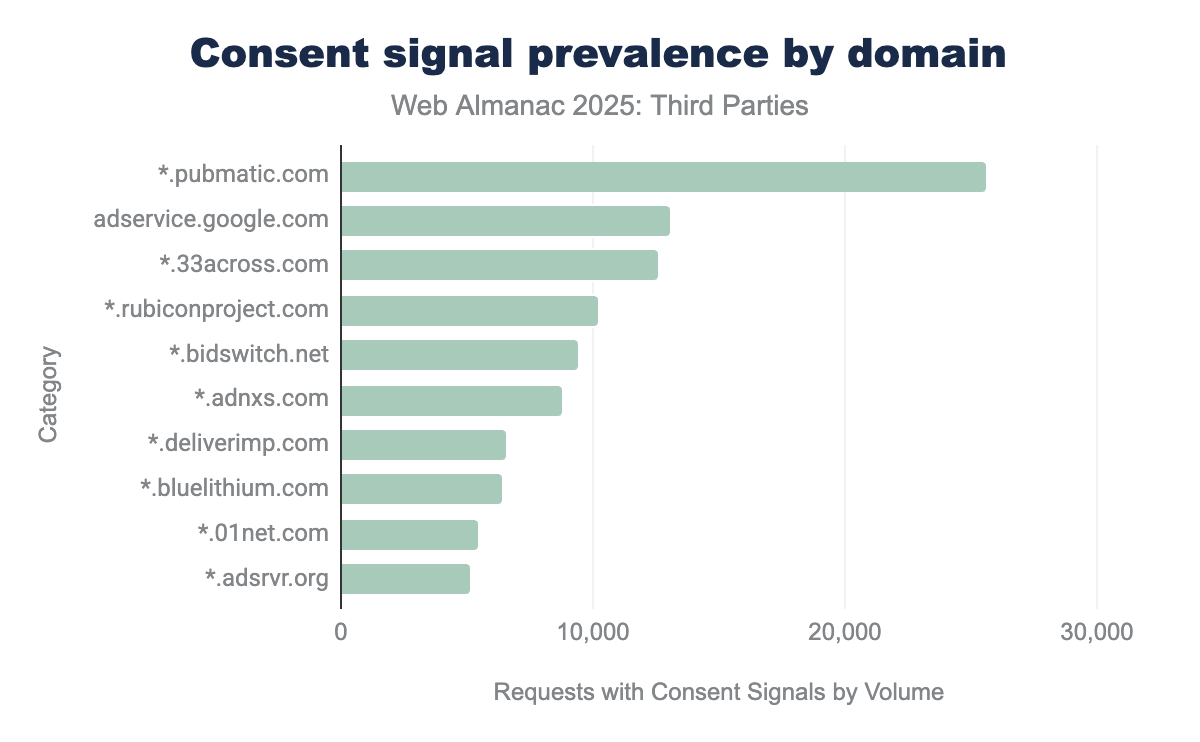

We examine consent signal prevalence in three dimensions: across different website ranks, among different third-party categories, and among the third parties receiving the highest volume of consent signals

Prevalence of consent signals across different ranks

We find that TCF is the dominant consent standard, particularly among higher-ranked sites where it reaches 36% compared to 18% across all sites. This aligns with GDPR’s stricter opt-in requirements for European users. The USP Standard is the second most prevalent, ranging from 9-17% across ranks, reflecting CCPA and state-level US privacy laws. GPP adoption remains minimal at 3-6%, despite being designed to unify consent frameworks across different jurisdictions and regulatory regimes.

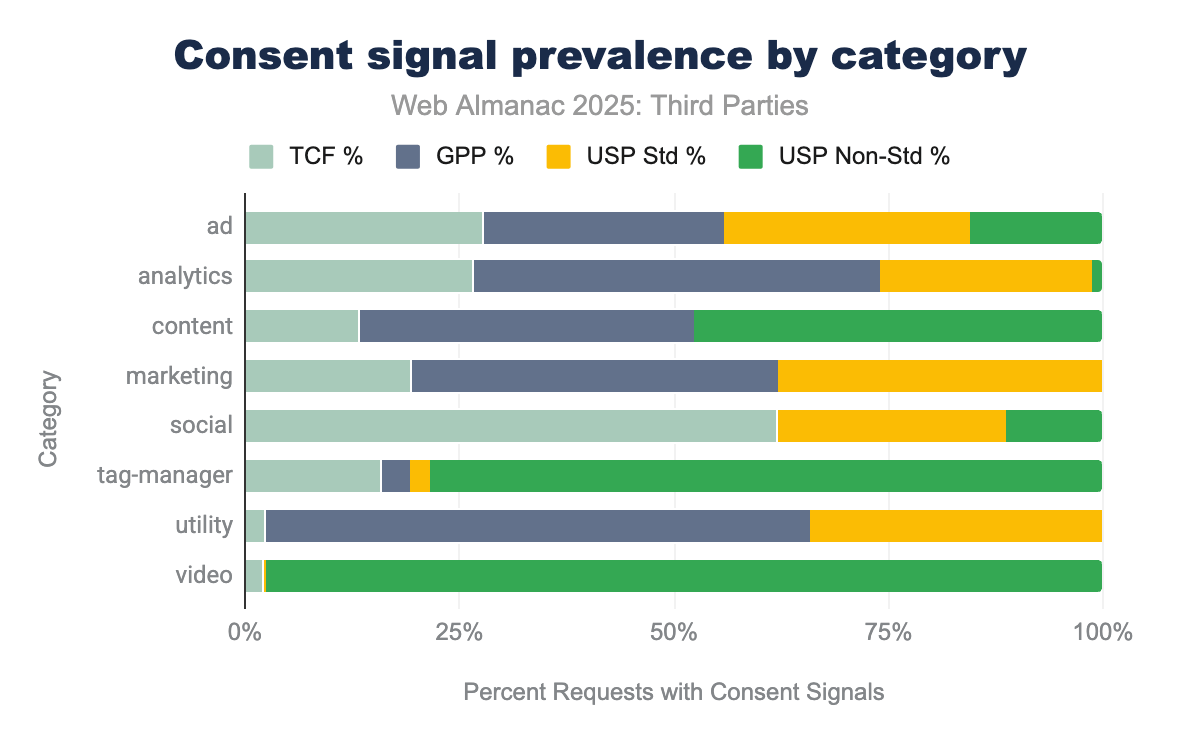

Consent standard distribution across different categories

We observe different consent standard preferences across third-party categories. Social services show the highest TCF adoption, while advertising vendors employ a more balanced mix of GPP, USP Standard, and smaller TCF shares. Analytics vendors predominantly adopt GPP. Marketing services show balanced adoption of GPP and USP Standard, with minimal TCF. Content and utility services rely primarily on GPP and USP Standard rather than TCF. Tag managers and video services diverge significantly from other categories, showing minimal adoption of TCF, GPP, and USP Standard in favor of USP Non-Standard signals—with video vendors relying on non-standard mechanisms almost exclusively.

Top third parties receiving consent

Among top-ranked websites, pubmatic.com receives the highest volume of consent signals, with adservice.google.com in second place. The majority of domains receiving the most consent signals are advertising and ad tech vendors—ad exchanges, DSPs, and ad servers.

Inclusion

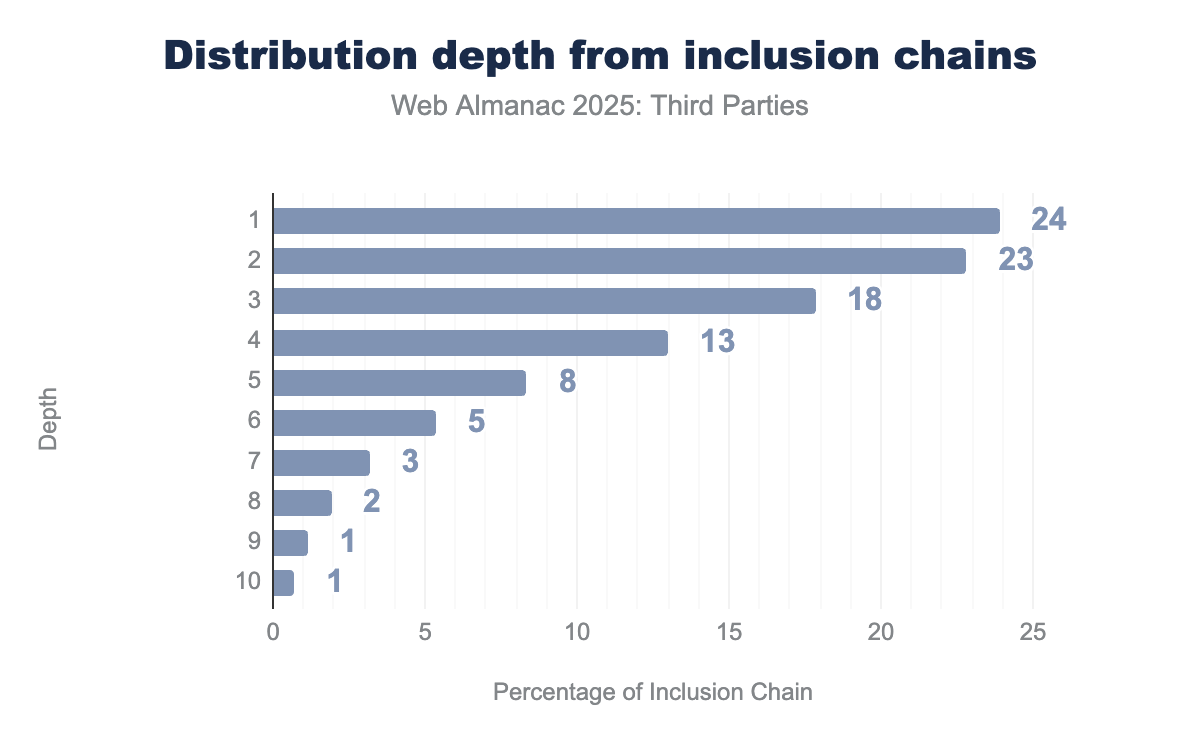

Recall from our earlier example that example.com (a first party) can include an image from awesome-cats.edu (a third party via an <img> tag). This inclusion of an image would be considered direct inclusion. However, if the image was loaded by a third-party script on the site via the XMLHttpRequest, then the inclusion of the image would be considered indirect inclusion. The indirectly included third parties can further include additional third parties. For example, a third-party script that is directly included on the site may further include another third-party script. In this chapter, we do basic analysis of the depths of inclusion chains of the third parties.

The median depth of the inclusion chain is 3 which means the majority of the third party include at least another third party on a web page. The maximum depth of the inclusion chain is 2,285.

Conclusion

Our findings show the ubiquitous and increasingly concentrated nature of third parties on the web. More than nine-in-ten web pages include one or more third parties. While the median number of unique third-party domains has decreased compared to the previous year, we observe a significant increase in the total number of requests from third parties, suggesting individual vendors are sending more requests per page.

In terms of consent standards, TCF is the dominant consent standard across all website ranks. Among individual third parties, pubmatic.com, adservice.google.com and other ad tech domains receive the highest volume of consent signals.

Finally, the increasing use of obfuscation techniques such as CNAME cloaking and server-side tracking reduces visibility of third parties in client-side measurements, suggesting our findings represent a lower bound on actual prevalence. The privacy, security, and performance implications of third-party use remain important considerations for web developers.